Olive Picking in Provence

Quite a few of you were interested in what happened around here on Thanksgiving. Even though my internet service is on it’s second week of vexing me, and I’d just assume go on strike like everyone else around here, in protest, I don’t think I’d get much sympathy, so I thought I’d better get my Thanksgiving post up.

I just saw a report on CNN that of all the countries around the world, the people in Israel eat the most amount of turkey, per capita, than anyone else. There are les dindes in France, but it’s almost impossible to find a whole bird, and one usually needs to be ordered in advance.

For one thing, one of those American-sized roasters would like be a tight squeeze in the average Parisian oven. And for another, well…there’s oysters.

I have no idea which country is responsible for consuming the most oysters, but this time of year there’s lugs of fresh oysters seemingly everywhere in this country, the one that I live in. And the amount that gets sucked down is astonishingly high. As Christmas gets closer, even the supermarkets get in the act and the wooden crates of oysters get stacked up outside, sometimes with men shucking a platter’s worth, offering ice-cold glasses of Muscadet to wash them down. I like the tradition of a bird roasted turkey, but I’ve also quickly adapted to the tradition of downing oysters and cold white wine, too. Our hostess have the foresight to reserve our oysters, and the poissonière was kind enough to ward off others with a stern Ne pas touchez! scrawled across the front.

Speaking of unconventional ways to celebrate holidays, this year, instead of staying home in Paris, we went to Provence. More specifically, to Draguignan, to pick olives. (On an odd sidenote; did you realize that there’s a sizable amount of people who read this site that don’t realize I live in France? I’m not sure why that is, but for my Christmas present, maybe someone can explain that to me. I thought it was fairly obvious…)

Down in the Var, my friend Mort Rosenblum hosts an annual olive pick for some close friends (the hardiest ones, no doubt) who are willing to stand in out in the blistery-cold rain, bundled up against the brisk wind, and climb rickety ladders to pluck tiny olives off their branches.

Actually, it didn’t rain the entire time. There were brief…very brief…moments of sunshine. (As in, the first few hours after we arrived.) But for the most part, the weekend was cold and damp.

Still, that didn’t stop the dozen of us from combing the hillside in search of the tiny black and green fruits, dangling from his gnarly old olive trees, their silvery leaves and plump olives catching any bits of the Provencal sunshine, and keeping our spirits up. Of course, anticipating sopping up the fresh-pressed oil—and the oysters—didn’t hurt much either.

Mort bought his house, nicknamed Wild Olives, years ago and wrote a terrific book, OIives, about the noble fruits themselves, which included not just stories about his visits to various parts of the world that grow olives and produce olive oil, with political, and sometimes religious, fervor. But it’s also his personal story how he rehabilitated these long-neglected trees and got them to produce the gorgeous little round olives that I was now yanking off them.

Aside from a semi-promising career as an olive picker (I’d grant him pro-status, but there was one unfortunate incident involving a broken strap and a giant pail of just-picked olives tumbling down a hillside), Mort is also a journalist and covers everything from wars to social injustices. Consequently, he’s done quite a bit of traveling, and while other travelers collect, say, snow globes or postcards, Mort’s office wall is lined with air-sickness bags from his travels all over the world. Unused, or course.

But there was no need to sickness bags with the delicious food we prepared for ourselves. In between picking olives, Jeanette, Mort’s wife, made sure there was plenty to go around and we gorged ourselves on just-opened oysters and bulots, tiny little whelks meant to be dipped in homemade mayonnaise and washed down with…what else?—cool white wine.

Except being in Provence, and although the weather wasn’t exactly cooperating, an astonishing number of empty rosé bottles magically appeared each morning scattered around the kitchen and dining room. Go figure.

We picked our little hearts out, wandering from tree to tree, striking up a quiet conversation from someone else, plucking olives from a neighboring branch, or standing alone on a steeped hill, engaged in the meditative act of stripping a branch clean of the shiny black fruits and filling the wicker baskets we’d all been walking around with for most of the weekend, strapped over our necks.

In the end, we’d picked almost twenty heavy lugs of olives, some black and bursting-ripe, while others were tiny, green and hard, which Mort insisted made the oil sweeter. I wasn’t so sure, but since he had a crew at his disposal, working our little fingers off, I think he was just happy to have all his trees stripped of their olives so we could race them to the local olive press, in nearby Aups.

Apparently the bakeries there make an especially good fougasse, and with all the olives and olive oil coming in and out of this relatively small village, it was easy to see how that was an entirely credible assessment. Unfortunately it was Sunday, and virtually everything but the local café was closed, so there we sat, toasting ourselves for doing such a good job stripping away an entire hillside of olive trees in just four days.

In that same village, there’s also a black truffle market there that I didn’t make it to, although a few folks escaped for a bit to watch the secretive wheeling and dealing between truffle hunters, who comb the surrounding forests for the prized black mushrooms, and local chefs and brokers, haggling over prices and quality.

I like truffles alright, but I’m not as ga-ga over them as others. I’m just as happy to slug down some fruity, thick olive oil dripped liberally over pieces of torn baguette, rubbed with cloves of fresh garlic. You can keep your pricey truffles; if there’s anything better than that combination of olive oil, bread, and garlic, that weekend, I couldn’t imagine it. No matter what the price.

So when we got to the mill, Jeanette had the brilliant idea of having a contest to see who could guess how many olives we’d all picked. I was certain we’d had a few tons—at least my neck felt like that, after having a basket loaded with olives weighing it down all weekend.

But being a pragmatist, I lifted a lug, compared it to an overstuffed suitcase (which, to be honest, I had far more experience with than lugs of olives) and simply tallied up what I thought was about right.

I guessed 650 kilos, and Romain guessed only 150 kilos.

I chalked his low stab at a number up to French pessimism, but la vache!, the little Frenchy was the closest. When we got to the mill and the fellow dumped our booty in the giant hopper, then weighed it, the scale revealed that we’d picked 301 kilos of olives. My neck was screaming for a re-count.

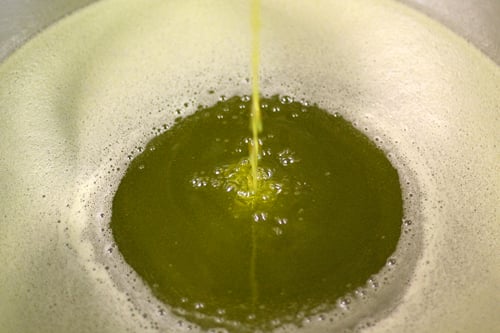

As they prepared the olives for pressing, we took a walk through the mill. The hyper-hygienic European Union had put the kabosh on those rustic, old-fashioned olive presses, but the modern machines were doing a bang-up job taking care of our olives, and we watched glugs and glugs of olives spewing out of the spouts. Mort could barely wait for a sip.

But we later found out that good things really do come to those who wait. And before driving away, the fellows at the press offered us a taste of some of their very own just-pressed oil, and we gladly accepted, sucking down as much of their oil as best we could, before heading back home.

That night, back at Wild Olives, we gathered round the fireplace to relax, happy to have plenty of leftovers to reheat from the Thanksgiving day fête. Oh yes, I forgot to mention what we ate for our Thanksgiving feast.

There was the aforementioned turkey, which was ordered in advance, which the poultry vendor took upon himself to stuff for us before trussing up. Since I had the task of making the stuffing, I was prepared to yank it all out and re-make le farce, American-style.

However when I opened the butcher paper, and saw the expert job that the volailler had done, I couldn’t bring myself to tinker with such perfection, which was a good thing. While most of the guests liked the Pepperidge Farm stuffing-mix batch we’d made as well (with a few contraband bags that were smuggled back from the states), like Romain’s prize-winning guess, the French once again proved that even in terms of stuffing, there are still a few things that some of us can learn from them.

Although I must confess: I love the Pepperidge Farm stuff. And so does Romain.

The rest of the meal was standard fare: baked acorn squash, cranberry sauce (also hand-carried from overseas), buttery mashed potatoes, and an assortment of desserts that included Baked brownies, pumpkin pie, pear sorbet, apple-mince–polenta crisp, all accompanied by an uncountable number of flûtes de champagne.

In a couple of weeks, my olive oil is being delivered to me from Provence. Each person gets one liter for all their help, and Romain gets two, since he won the contest. There were 53 liters in all, so I know when I go back and visit Wild Olives, there’s going to be plenty of good olive oil on tap.

In the meantime, I’m waiting for my very own bottle to arrive, which should coincide with Christmas, and that all-important annual holiday—my birthday!…just two days after. I’ve finally shaken the chill of standing out in the cold rain, reaching and picking, and my neck is almost recovered. (For my birthday, I could use a massage, fyi….)

But in spite of the hardships, which included a dulling gueule de bois the morning after our Thanksgiving banquet, it was a lot of fun and there was truly something to give thanks for—that I’m lucky enough to have such terrific friends, and to be able to gather around the table with them during the holidays. To be able to soak in all the beauty of Provence, and to soak in plenty of just-pressed olive oil, too.